By JESSE GRAHAM

QUICK thinking helped veterinarians from Healesville Sanctuary fix up a koala joey last week, which had two limbs broken after being hit by a car.

On Thursday 30 July, Arthur the nine-month-old koala joey was brought in to the glass-walled surgical theatre at the sanctuary’s Australian Wildlife Health Centre (AWHC) to go under the knife.

Arthur had been brought in by Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP) officers – who also named him – the day before, after being flagged down by a member of the public near Powelltown.

The joey, who would have only recently started leaving his mother’s pouch, was found dehydrated and limping by the side of the road – it was revealed later that one of the koala’s arms and one of his legs were broken, injuries vets believe were caused by a car.

At about 11am on Thursday morning, veterinarians Meg Curnick and Franciscus Sheelings joined vet nurse Gerry Ross to prep Arthur for surgery.

Speaking to media before the surgical preparation, Dr Curnick said that koalas generally became independent from their mothers at six months – at nine months old, Arthur would have been on his own very recently.

“He’s a young koala and he’s at the age where he fairly recently became independent from his mother,” she said.

“Of course, our roads now go through koalas’ habitat – to find more boughs to eat, they often have to cross roads and they never evolved to have roads, so we think that’s most likely what happened.”

Pointing out the broken limbs on a computer screen, Dr Curnick explained that, while the arm was expected to heal in a splint, the leg needed to be operated on.

The fix was to pull the bone ends out and put them back in place, screwing pins into the bone, which would be fixed by an external frame.

The pins, she said, were to stop the bone rotating during recovery – leaving the animal with a foot facing the wrong way.

“It’s a relatively simple fracture to fix in a lot of ways,” Dr Curnick said.

“But the trickiness is involved that it’s a young animal, so the bones are quite brittle – it is a small animal, and the anaesthetic is trickier than with domestic animals, but hopefully it should go well.

“We never say it will definitely go 100 per cent well, because there are always difficulties with surgery, but we’ve got a fairly good feeling about the outcome.”

Dr Curnick said that, should Arthur pull through the surgery, recovery would take between four to six weeks, depending on his behaviour during that time.

It would then be assessed whether he could be released, or if he’ll stay in captivity at the sanctuary.

“He’ll be with us for a little while,” she said.

“We’ll have to make an assessment as to whether we can be absolutely sure that his welfare will be fine if he’s back in the wild.

“If not, sometimes what happens is we keep them in our collection.

“We’ll do everything we can to ensure he has a really good future, either way.”

Gathering around a medical table at the AWHC, the vets worked in front of photographers and television crews to anesthetise the injured koala, before shaving the fur off of the soon-to-be opened leg.

Dr Sheelings then wrapped the koala’s foot, explaining that the fur couldn’t be completely shaved away from the foot, and the site of the surgery had to be as sterile as possible.

Before taking the koala into the sterilised surgical theatre, Dr Sheelings also took a swab from the animal to test for chlamydia – which is often rife in wild koalas, and can be a risk to other koalas in captivity.

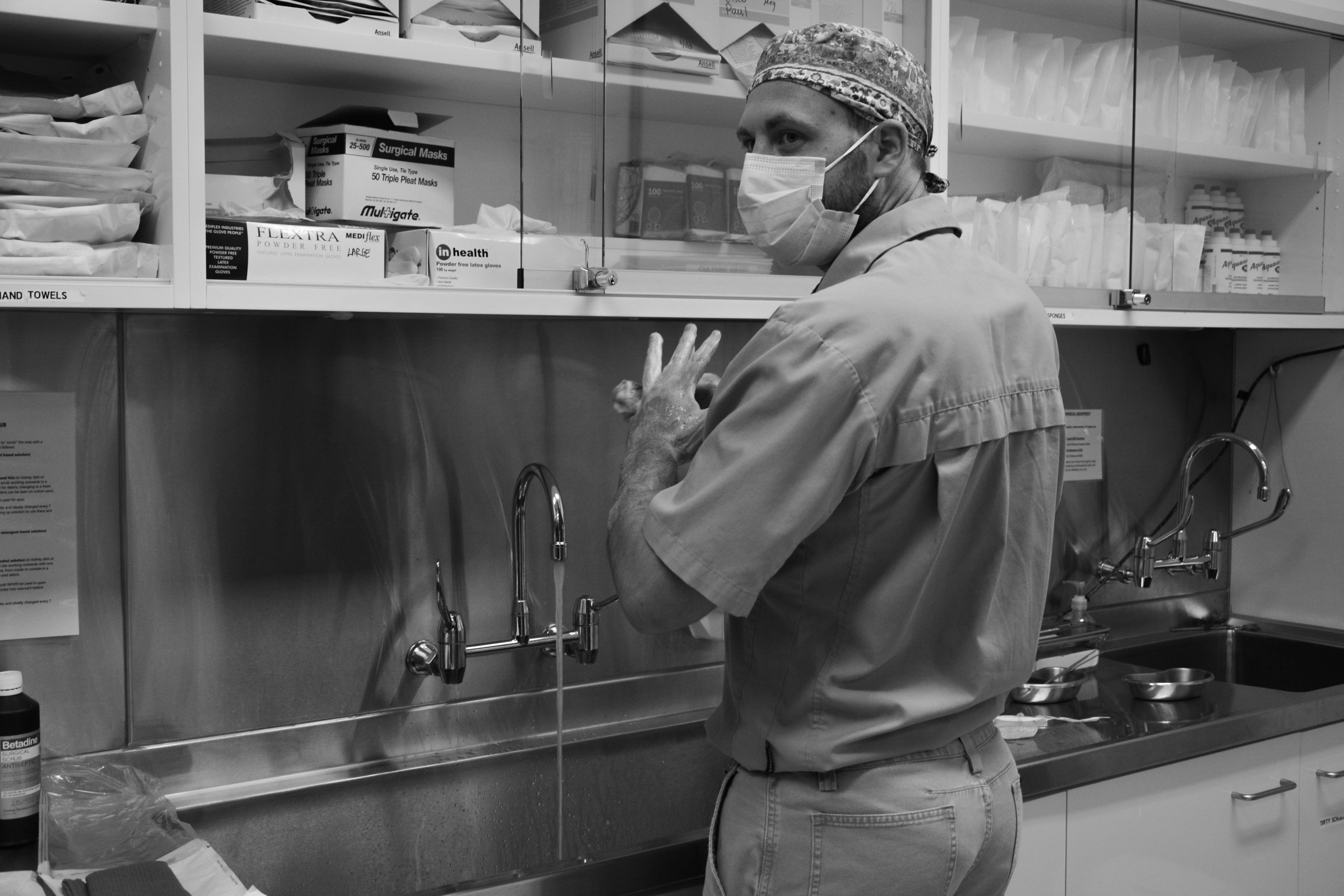

Arthur was then carried into the surgical theatre and placed on the table, while Dr Sheelings scrubbed up for the surgery.

Media then moved to the visitor’s area of the AWHC, where news crews filmed piece-to-cameras on the surgery beginning and photographers – including this reporter – snapped shots of the first incisions.

Dr Curnick said the biggest concerns for the vets would be keeping Arthur’s vital signs normal while the leg was being repaired, and to be gentle with potentially more fragile bones, while still applying enough force to get the pins in.

“When he recovers, our concerns are going to be keeping him pain free as much as possible, starting to get him to eat, because he needs calories to fix those bones, and preventing infection – so keeping him very clean and keeping his environment clean, giving him the best chance to recover,” she said.

She explained that Arthur would be paired with a teddy bear through his recovery, to help calm the animal and simulate the feeling of his mother.

“We always like to have our baby koalas having something to hug – because, naturally, if they’re worried or stressed, what they want to do is cling to a tree branch, or, in the case of a very young one, they want to cling to their mother,” Dr Curnick said.

“A teddy bear provides a bit of a mother substitute – Arthur was just about becoming independent from his mum, a teddy bear will give him some comfort and some security.”

However, after the first incisions began, Dr Sheelings discovered that the bone wasn’t just broken, but had split – meaning that simply pinning the bone was no longer an option.

Dr Curnick then had to scrub up and assist in the surgery, while they assessed their next steps.

The mood became tense in the AWHC, as media and visitors waited to hear whether the surgery would turn out well for Arthur.

After a few minutes of uncertainty, Dr Curnick gave the thumbs up to those waiting on the other side of the glass – her signal that it was all back on track.

About an hour after starting, Arthur was stitched up and had his broken arm splinted, before being brought back to consciousness by the vets.

“It proceeded a little bit differently than we thought it would,” Dr Curnick said.

“Because what we found when we got in there was the top bone, nearest the hip, had a split up it that wasn’t apparent on the initial X-ray.

“What that meant was we weren’t then able to put the pins in to do what’s called an external fixation frame – because the split was right where those pins would have to go in, and that would have turned the bone into sawdust.”

The solution was using more wires to stabilise the bone, while pinning the middle of the bone.

“After a bit of a push and shove and some elbow grease, it’s come back together pretty well,” she said, relieved.

“Unfortunately, sometimes, with fractures, you do get these fissures that you can’t see on the X-ray, unless you’re very, very lucky.

“It’s one of those things that you have to play by ear, play by the seat-of-your-pants a little bit when you get in there.”

Dr Sheelings, after the surgery, told waiting media that Arthur was expected to recover from the surgery well, and that helping to heal animals surgically was one of the best parts of his job.

“The best part of my job is being able to operate on animals that typically come to us because of human interference, so it’s great to then fix him and then release him,” he said.

According to the sanctuary, the hospital sees more than 1500 animals each year, brought in for emergency help from around the state.

The success of Arthur’s surgery is just the latest for the institution – though hopefully not the last.