“The history of Coranderrk did not end in 1924.

“The stories of Coranderrk continue today through descendants and also by Wandoon Estate Aboriginal Corporation (WEAC) caring for the Country at Coranderrk.

“The history of Coranderrk is powerful in speaking to the realities and injustices of the past and has an important role in truth-telling both locally and nationally.”

This is what a descendant of the Coranderrk residents Brooke Wandin said when Star Mail interviewed her about Wandoon Estate Aboriginal Corporation’s art exhibition ‘yalingbuth yalingbu yirramboi yesterday today tomorrow’ in September.

2024 marks the 100th anniversary of the closure of the Coranderrk Aboriginal Station.

Coranderrk was central to the history of Victorian First Nations communities as it was one of the six aboriginal reserves that were established in Victoria to save First Nations people from extinction.

The establishment of Coranderrk affected other Aboriginal communities in Victoria and five more reserves were set up across the state.

After getting through a hard period, Coranderrk Aboriginal Station was officially closed down in 1924.

To commemorate the 100th anniversary of the closure of the Aboriginal Station, Star Mail decided to delve into the history of Coranderrk.

Star Mail interviewed three Coranderrk residents descendants, David Wandin and Brooke Wandin who are the great-grandchildren of Robert Wandin, one of the leaders of the Coranderrk community as well as Healesville grown man Andrew Peters, who is an associate professor of Indigenous Studies at Swinburne University.

Assoc Prof Peters said he is a descendent of the Yarra Yarra, Yorta Yorta and Ngurai illum Wurrung peoples.

“Yarra Yarra is a name that is used to refer to some former Coranderrk residents and their descendants, who are not traditional owners, but are recognised as having strong links to Coranderrk and surrounding areas,” he said.

“My great-grandmother, Lizzie Davis, was one of the last residents of Coranderrk.

“As it is to all descendants, Coranderrk is a place of great pride and connection to me. I feel blessed to have grown up in Healesville and with this connection to Coranderrk, and love sharing this with my sons now.”

Before the emergence of Coranderrk

After 30 years of the first wave of British settlers arriving in Victoria, the white population grew rapidly and it reached about a half million in the 1860s.

Over the same period, the population of the First Nations reduced dramatically from 60,000 people to just 2000 due to several factors including diseases which the newcomers brought into the land and the conflicts between the new settlers and the Aboriginal people.

Before the arrival of the newcomers, Victoria was a patchwork of 36 clans, each with their own language and territory, and was the most populated region in Australia.

The Kulin Nation consists of five language groups who are the traditional owners and lived in what is known as the Port Phillip region; Boonwurrung (Boon-wur-rung), Dja Dja Wurrung (Jar-Jar-Wur-rung), Taungurung (Tung-ger-rung), Wathaurung (Wath-er-rung) and Woiwurrung (Woy-wur-rung), commonly known as Wurundjeri.

Woiwurrung clans leader Billibellary appealed to assistant protector William Thomas for a grant of land, proposing that his people could make a place for themselves in the new colonial order by living sedentary lifestyles and farming the land.

Although it didn’t go successfully, the relationship the clans leader built with the assistant protector would take a big role in establishing the Coranderrk Aboriginal Station later when Billibellary’s son Simon Wonga approached William Thomas to request land for his clans in 1859.

The new ngurungaeta (leader) of the Woiwurrung clans, Wonga, explained Aboriginal people were enthusiastic about being successful and actively accepted the culture of the white community.

Thomas was persuaded by Wonga’s argument and helped Wonga and his clans obtain land.

The Victorian Government convened the Aboriginal Protection Board to address the plight of First Nations people.

In the same year, Wonga and the Taungerong people established the Acheron station in the north of the Cathedral Range.

However, in the following year, after they put an effort to plant and grow vegetables and wheat, they were ordered to relocate by the government, to the Mohican station located south of Acheron, where it was cold, inhospitable and unfit for farming.

They explained it to Thomas and he pleaded for the government’s help but it wasn’t accepted and they were forced to leave Acheron.

Establishment of Coranderrk

While the Woiwurrung clans were struggling to get a safe place, Scottish Presbyterian lay preacher John Green and his wife Mary Green became good friends of the First Nations people.

The two Greens arrived in Victoria in 1857 and started to preach for First Nations adults along with opening up a school for their children in Yering.

In 1861, taking a job with the newly formed Central Board Appointed to Watch Over the Interests of the Aborigines in the position of General Inspector, John Green attempted to establish another station like Acheron where both the Woiwurrung and Taungerong clans might settle.

In March 1862, the Woiwurrung clans and the Green family walked from Yering to Acheron but they couldn’t settle there because of the local squatters’ disturbance.

In the next year, Green applied to the Central Board for permission to return to Woiwurrung Country in order to establish a new reserve on the Yarra.

They created a new path, now known as Black Spur, while walking back to the Yarra Ranges.

In March 1863, they finally arrived at the site they had chosen in an area at the confluence of the Yarra River and the Badger Creek.

They set up camp and named the site Coranderrk which is the Woiwurrung name of Christmas Bush (Prostanthera lasianthos), the native plant of the area.

Assoc Prof Peters said the reserve was part of the protection era in Australia, where the primary aim seemed to be allowing colonial expansion.

“Reserves and missions were established to get Aboriginal out of the way of that (colonial expansion), and to not impede it,” he said.

“On face value, their establishment was quite a negative thing – our people were displaced, and culture effectively outlawed.”

Although they settled in the new place, Green and Coranderrk residents were aware an official confirmation of the land’s reservation needed to be published in the government’s gazette.

In May, Wonga and his younger cousin William Barak noticed Governor Sir Henry Barkly would hold a public reception in honour of Queen Victoria’s birthday.

Wonga with a deputation of 15 Woiwurrung, Taungerong and Boonwurrung people walked to Melbourne and gave handcrafted rugs and blankets for the Queen and traditional weapons for Prince Albert.

Being touched by the surprising presents, in the following month, a notice appeared in the Victorian Government Gazette announcing the Governor had ‘temporarily reserved’ 2300 acres, thereby formally establishing Coranderrk as an Aboriginal reserve (extended to 4850 acres in 1866).

Copies of a letter from the Queen’s secretary were sent to the Kulin later that year, conveying the Queen’s thanks for Wonga’s address and her promise of protection.

This led the Kulin to understand that their request for land had been granted by the highest authority, the Queen herself, via her regent, Governor Barkly.

This event not only acted as proof of the Kulin Nation’s entitlement to the land but also demonstrated the effectiveness of deputations’ handwritten appeals.

Ms Wandin said Wonga had great communication skills not just with immediate family but also with neighbouring Aboriginal tribes as a leader.

“He would have been relying on all of the old ways that he was taught as a child growing up,” she said.

“The Aboriginal way is about being respectful to each other including all elements of country.”

Mr Wandin said First Nations leaders including Wonga, Barak and Billibellary had already been trade ministers and foreign policy ministers between mobs.

“All the government systems we’ve got in today, First Nations people already had that system in the past,’ he said.

“There was always negotiation going on between mobs regarding planning, gathering, conferences, several disputes and arranged marriages.

“Collective groups of elders were our ministers.”

Impacts of Coranderrk across Victoria

Coranderrk residents wanted to prove to the white community they could live like the white people did.

Through the management of superintendent John Green and First Nations leader Simon Wonga, Coranderrk was becoming a productive and profitable village in its early years, with self-sufficiency.

“What’s interesting and inspirational about the Coranderrk is lots of different Aboriginal families were all working together,” Ms Wandin said.

Green’s management supported the Kulin peoples’ autonomy in developing the station and was respectful of Indigenous traditions.

Residents’ literacy increased and a better diet led to improved health.

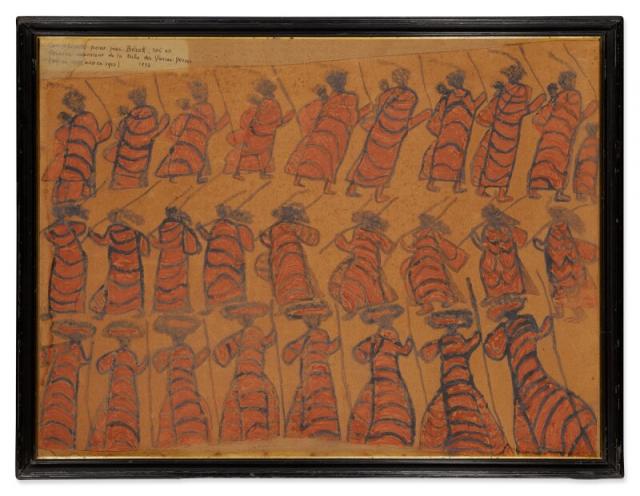

Coranderrk became a popular tourist destination and the sale of baskets, bags, boomerangs and skin rugs, made by women and elderly men, contributed significantly to the station’s income.

Inspired by the success of the Coranderrk, other clans and missionaries requested land from the Aboriginal Protection Board and five other reserves across Victoria were built by 1865; in the west, Framlingham, Lake Condah, in the north, Ebeneezer and Cummeragunja and in the South, Lake Tyrers and Ramahyuck.

Assoc Prof Peters said in his view, while the intentions of missionaries may have been honourable at the time, which is debatable, he doesn’t think they had a positive influence overall.

“There are some Aboriginal people who embraced Christianity from the outset, and this may in part be due to their existing belief systems – spirituality plays a vital role here,” he said.

“However, in broader terms, the imposition of Christianity meant that Aboriginal spirituality was downgraded to almost ‘child-like’ which was in line with the broader British/European thinking of Aboriginal Australians as sub-human.”

In Ramanhyuck run by a German missionary reverend Friedrich August Hagenauer, all forms of Aboriginal religious ceremony were banned.

Ms Wandin said Green was one of the kinder missionaries who was in a tough situation to keep both the government and the Coranderrk community happy.

“What’s interesting is that even though Aboriginal people learnt how to read and write and learnt about Christian prayer, this site (Coranderrk) was still able to maintain culture,” Ms Wandin said.

“For example, a lot of the people continued to make traditional objects and gift them to people but they also sold them to create income for themselves.

“Whilst there’s not a lot of language that’s been recorded, some language has been recorded, so we know that traditional practices were surviving.”

Beginning of crisis

Even though the Aboriginal Protection Board supported Wonga’s initiative in establishing Coranderrk, the Board insisted on controlling their activities.

In 1872, the board invested in a new venture of Coranderrk to create a lucrative industry of harvesting hops to make beer.

The residents built kilns and filled their fields with hops plantations.

The board promised Green and the Coranderrk residents that the profits would fund a new hospital.

During Green’s tenure, the station was becoming more and more stable with the success of its hops plantation.

As the hops crops were going successfully and the board found the value of it, the board wanted to take control of Coranderrk.

The board employed a white overseer who took control from Wonga and Green and brought in white labour and then paid wages only to the white workers.

In the mid-1870s, along with the pressure from the local squatters who wanted the land of Coranderrk and insisted on the closure of it and the Board’s greed for taking more control, the board started to think about Green’s managing position.

In 1874, two major changes occurred in Coranderrk.

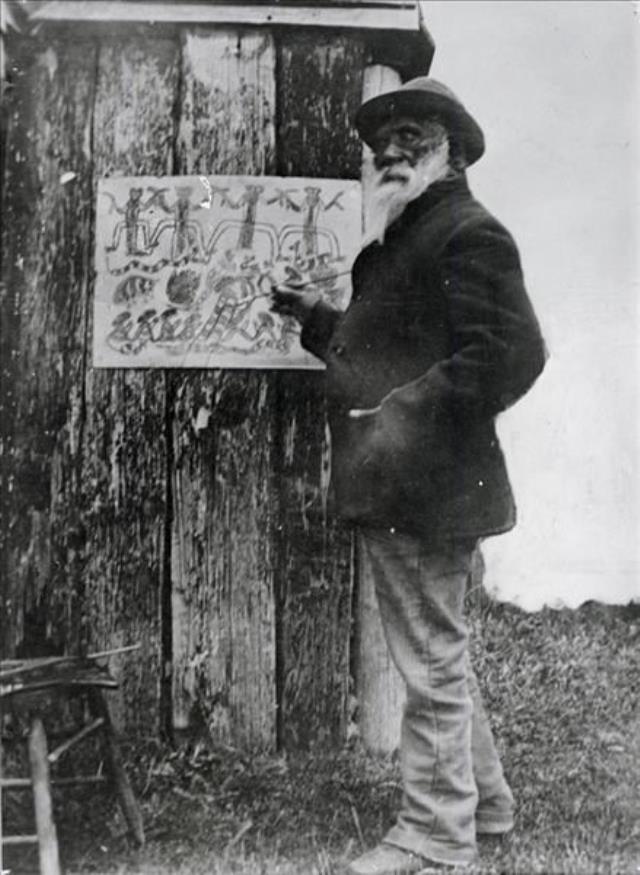

John Green resigned as superintendent and Simon Wonga died of tuberculosis and his cousin William Barak became the next ngurungaeta as he didn’t have any sons.

Ms Wandin said Barak’s leadership was similar to that of Wonga’s as they were born at a similar time.

“They were both born around the 1820s when there would have been very few European people in Australia,” she said.

“When they were little boys, all they saw was the Aboriginal world.

“They learnt the old traditional ways and they carried that with them as they got older.”

Even after his resignation, Green still lived near the Coranderrk and tried to help the Coranderrk community.

The new superintendent was a lot more strict and harsh on the residents, who followed the advice of the Board and focused on punishing the residents and directing their everyday lives.

Food and clothing supplies were cut, houses became run-down and the residents could not access proper medical treatment.

The board sold the entire hops plantation and the government kept the profit, not investing the medical facilities for the Coranderrk residents.

Peaceful campaign

In response to these worsening conditions, the Coranderrk community decided to protest peacefully with the memory of the success of Wonga managing to persuade the Queen.

On 7 July 1875, William Barak, Thomas Bamfield, Robert Wandin and others led a delegation of Coranderrk residents on the 67-kilometre walk from Coranderrk to Melbourne seeking Green’s reinstatement.

It was the beginning of the two-year campaign of petitions, strikes, deputations and lobbying with politicians and the press.

Barak and Bamfield also worked with concerned European settlers to make the public aware of their demands, including Anne Bon who wrote an impassioned letter to the premier of Victoria.

Despite the campaign, the board’s decision to shut down Coranderrk became more certain.

However, the government could no longer just ignore the campaign as it became so effective and even found allies from the white community.

In 1881, Chief Secretary Graham Berry appointed a parliamentary inquiry to investigate the Board’s management of Coranderrk and to decide upon its future.

The inquiry lasted for two and a half months, from late September to early December 1881.

Taungerong clan head Thomas Bamfield, who was also the chief aide of Barak, became heavily involved in disputes against the Board.

He was the first Aboriginal witness to speak at the 1881 Parliamentary Coranderrk Inquiry.

Bamfield focused on explaining the station’s ability to be self-supporting and the expectation of proper maintenance and protection in return for the loss of their ancestral lands and cultural autonomy.

The nine commissioners, including eight prominent men and the redoubtable wealthy widow Anne Bon, held 10 hearings, three of which were held at Coranderrk.

They examined 69 witnesses, both Aboriginal and European and asked 5349 questions.

The inquiry had significant influence as its findings had the potential to trigger a reform of colonial policies, not just towards the management of Coranderrk but all of Victoria’s Aboriginal population.

Six months after the inquiry, Bamfield was sentenced to be imprisoned for 30 days with hard labour.

However, Anne Bon helped him by writing a letter to the chief secretary with a petition including the signs of seven prominent parliament members, which embarrassed the board as well as the three senior magistrates who had sentenced Bamfield’s imprisonment.

Bamfield was released after three days of imprisonment.

Half-Caste Act

In 1886, the Aboriginal Protection Board came up with a final solution to sell off Coranderrk and other reserve lands.

German missionary reverend Friedrich August Hagenauer, the missionary for the Ramanhyuck Aboriginal Mission, was employed by the board.

He drafted a new law, the Half-Caste Act, which stated any of the First Nations people who had any white ancestry and were under the age of 34 were considered not Aboriginal and were therefore exiled from any mission or reserve.

Both Premier Berry and Anne Bon agreed that this policy was progressive.

Assoc Prof Peters said ‘progressive’ is one word that colonialists use to justify expansion and cultural damage, and is tied closely to the goals of capitalism, money before culture.

“I can’t assume to know what Anne Bon was thinking, or what changed her thinking,” he said.

“To me, her actions indicated that the political system – Woiwod’s ‘Black Hats’ – had too much power to fight.

“The Half-Caste Acts to me is one of the greatest examples of colonial power exerted on Aboriginal peoples, and however, I look at it I cannot see any positives of it for our people.”

The result was the ultimate destruction of Coranderrk as well as many other Aboriginal communities including Framlingham, Lake Condah and Lake Tyers.

Barak and his people had no one to turn to, and they were forcibly moved to Lake Tyers.

After the issuing of the Half-Caste Act, the number of Coranderrk population kept decreasing, and the Coranderrk Aboriginal Station was eventually shut down in 1924.

Shut down and the next stages

After leaving Coranderrk, John Green established his own hop garden on the banks of the Graceburn in Healesville.

He was also a Justice of the Peace sitting regularly in the Healesville Magistrates Court.

John Green led the deputation to the public works minister to present a petition for the formation of a Healesville Shire and when it was granted, he became an inaugural member of the Healesville Shire Council in 1887.

Green Street in Healesville was named after John Green.

Assoc Prof Peters said John Green had a remarkable record at Coranderrk, and was held in very high esteem by the Aboriginal people at the time and their descendants.

“Mum (Aunty Dorothy ‘Dot’ Peters AM) always used to talk to me about the respect he had for and received from the residents of Coranderrk,” he said.

“My guess is that history may have been very different if he was allowed to stay in charge.”

In the 1990s, Indigenous Land and Sea Corporation purchased the property of the part of Coranderrk and handed it over to WEAC, which was set up to manage the property run by the Wandin family, the descendants of Robert Wandin who was one of the leaders of the Coranderrk residents as well as the nephew of Willam Barak.

WEAC has managed the Coranderrk since then.

Brooke Wandin and David Wandin are both directors of the WEAC.

“It’s a big responsibility to care for this property, not only for my family but also for many different other Aboriginal families whose ancestors lived here,” Ms Wandin said.

Coranderrk ancestors’ legacy: peaceful reconciliation

Ms Wandin said WEAC aims to keep the legacy of the ancestors of the Coranderrk in the reconciliation movement.

“For example, when we’re thinking about planning for the future here at Coranderrk, we always think about what our ancestors have done in the past, and we try to be guided by those same values,” she said.

“The Coranderrk residents were pretty clever, they wrote letters and walked into Melbourne, went straight to the government to talk to them, which was highly unusual for the time.

“So we try to follow in their footsteps as best as we can.”

David Wandin said it’s important to adjust the modern methods with traditional methods to get a better outcome in managing the land.

“I challenge everybody to try and think about it because the chemical company says this will do the job but that’s not the way we manage country,” he said.

“We didn’t have chemicals, our main farming tool was fire but the right fire.

“Our other farm tools were the animals but because of lots of things that happen today, it’s very hard to get it back to its natural state. We don’t have the small digging animals, most of them are very rare or extinct.”